Coming down from the mountain

Integrating a magical year into “real life”

Since I last wrote to you about gardening I’ve made a lot of progress on this year’s prep. First I soaked eggplant and hot pepper seeds between wet paper towels inside sandwich bags until they sprouted, leaving the baggies wrapped in a dishtowel on the counter above the dishwasher for extra warmth. I planted the strongest ones in seed starting mix along with seeds for several kinds of tomatoes. I prepared soil in exactly the right number and combo of those little black plastic multi-plant containers that garden plants are sold in to fill an aluminum baking tray that I happened to have in the basement, the disposable kind that come in a pack of three at the grocery store that you might take to a potluck where you don’t want to wait around until the end to claim your baking dish. To keep myself from going overboard as usual when starting a garden and to force thoughtful choices I somewhat arbitrarily chose this tray as my limit, which in its current configuration (with a hodgepodge of different sizes of trays) can hold 29 seedlings.

The plants are labeled with wooden chopsticks, the kind you get in sushi takeout and have to break apart. The chopsticks were also supports for a temporary Saran Wrap roof, regrettably made necessary when Gary the dog-cat started sniffing around the eggplant seedlings. I consoled myself that the swath of plastic involved was a) not in actual contact with the soil, though some moisture may have accrued there and rained down, and b) not that much plastic in the grand scheme of things, considering the bushels of produce I expect this little tray’s inhabitants to yield. Cross your fingers!

When seedlings had all emerged I switched from the plastic wrap to an aluminum foil wall on one end of the tray, trying to reflect as much light as possible toward the tiny plants. Gary started batting at the foil instead, and when I took that away he started removing the chopsticks. It turns out he doesn’t want to bother the plants at all but enjoys the outsized reaction he gets from me when I think he’s going for them. Gary never passes up learning a new skill if it can get him some attention. (See also, turning on water in the bathroom sink, taking the lids off banker’s boxes, and opening the kitchen door if the deadbolt isn’t engaged.) At this point some of the information about which plants are which as been lost, but at least I can still tell the difference between eggplant, tomatoes, and peppers. We’ll find out their varieties when they set on, I guess. It doesn’t matter; they are alive and know their plan even if I don’t.

Next year I plan to level up the process on seedlings by investing in a soil block maker. This ingenious tool uses pressure to make little cubes of seed starting material that hold their shape, including a little divot for your seed or sprout. I recently learned how much better it is for the seedlings, in addition of course to not creating any more plastic trash or microplastics. As you have probably seen if you have ever bought tomato plants, when a seedling is growing in one of those black plastic trays and the tip of the root hits the plastic wall, it turns one way or the other and keeps growing, around and around. The poor little plant uses lots of resources to grow more roots to try to get more water for itself, making useless circles. By contrast when a tiny root reaches the edge of a soil block, it encounters air—and automatically goes dormant, a process called “air pruning.” I love that this is becoming a widespread practice in the nursery business because it means soon I’ll be able to buy plants in that format from the small farmers around Ann Arbor who start their own plants and sell their surplus seedlings at the farmer’s market along with their produce. (Who knows, maybe they were already doing that last year? I was away.) Before next year I plan to acquire the doohickey for making soil blocks, but for now my recycled black plastic nursery trays will have to do—and as always I’ll be extra careful not to chip them up as I work with them, to keep those flakes of plastic out of the soil.

In Ann Arbor we are lucky to have very good city-wide curbside composting. Our curbside bin for compost is nearly twice as large as our trash and recycling bins. Into it we may deposit not only yard trimmings and weeds but just about any foodstuff and any compostable foodsafe products, including paper towels and the cardboard circle that comes in a pizza box, absorbing the grease of the pizza such that it cannot be recycled like the rest of the box. In exchange for sending all of our yard and food waste into the central compost pile, we are entitled to an approximate pickup truckful of finished compost once a year by showing our ID with an Ann Arbor address. This compost isn’t perfect—sometimes it reveals that others have not done such a good job following the rules, containing as it often does little bits of degraded plastic or immediately sprouting things like poison ivy when water hits it. But for the most part it’s decent soil, and with a few shovelfuls of composted manure mixed in it does the trick. I do my best to make sure only good stuff goes in, so good stuff will come out.

I’m thinking about it because there is a moving project to do in the back yard, and an exchange of soil. There will be one particular week in May in which to accomplish it, after the peas and radishes currently in the northern raised bed have done their thing and before it’s time to transplant the tomatoes. The reason? That bed, sitting not far from the long-ago victory garden I recently mentioned, is both too shaded and too close to the enormous black walnut tree for most plants to thrive there. Countless squirrels have enjoyed it as an elevated dining room and left behind the detritus of their walnut meals, adding more juglone to soil already contaminated by whatever bits and bobs the tree rains down throughout the season and by tree roots reaching up into the box despite its plywood floor. It’s time for a fresh start, with new dirt, over by the other raised bed where the sinister tree can’t reach. We’ll harvest the argula and radishes and peas I’ve recently planted—I barely tilled the soil, knowing these last denizens of the bed won’t care to root themselves too deeply—and then use shovels to fill the wheelbarrow with everything that’s left in the box. This old soil will then be chucked down our tiny hill a little ways to fatten up the small ridge where goldenrod likes to grow. Once again I’ll toss handfuls of a variety of wildflower seeds to encourage a bit of color diversity, but I will be not at all surprised when by September it’s once again a wall of fuzzy gold. The birds, especially the finches, love the seeds, and we enjoy the privacy from the neighbors behind us whose patio door stares up the hill toward our sunroom. (By now they must surely have some running jokes about my ratty grey bathrobe.)

But even though the box will have been reset, maybe there is something dormant in the soil it now holds, something that couldn’t come forth and prosper in the current conditions, that will find its tiny footing in the shadow of the goldenrod deadheads and spring forth. Perhaps seed seeds I sowed four years ago when the bed was first erected and filled will finally have their day in the sun. I had to look up how long ago we built those beds by looking at photos and was shocked to learn it was only in 2021. I could’ve sworn it was ten years ago, not four. Time moves differently in middle age. Everything is simultaneously “just last year” and forever ago, the formats of hard-won knowledge interwining with echoes of memory to create an impression of the past that is hardly more reliable than predictions of the future. No doubt I have forgotten much of what I sowed there. Perhaps one August morning I’ll laugh myself silly when I find a bounty of peppers, tomatillos, and okra growing willy-nilly among the vinca that fills the slope down to the back fence.

Meanwhile in the other bed, the one that doesn’t need to move, carrots are starting to come up, and green onions. The soil there is rich and black and required more work to turn over because I had to cut deeper, its surface a tangle of withered parsley crowning a web of roots below, with copious piles of rabbit and possum poop lying between. It seems that in letting it lie fallow last year I created a secret place where small mammals could hide, feast, raise young—and they have repaid me with nitrogen. Under and among the remnants of parsley I discovered several impressively large and straight carrots that I didn’t notice in the fall, carrots that had seeded themselves from past flowerings or from seeds I planted in the past that hadn’t germinated. They were indistinguishable from the parsley at harvest time because I wasn’t looking for them. Left to freeze and thaw repeatedly over the winter, they had turned to mush by the time I handled them, but they indicated an even greater bounty: surely some other, smaller, more easily digable carrots were too good to pass up for some of those rabbits. The bed was likely fullish of them. My point? I’ve done okay growing carrots in the past, but never produced specimens as grand as the garden managed to do without my constant intervention. So this spring I’ve sown carrots again, vowing not to fuss over them, but to let them find their rooty ways into the fullness of last year’s volunteers. I will do the bare minimum for them: show up, keep watering, remove weeds that would stand in their way or steal resources, and let them grow as they will. I will not prod and jiggle at them in search of early hints about what they’ll turn out to be—nothing can grow when you constantly uproot it to see if it’s growing.

My body and brain are like those little air-pruned roots, grateful that I tipped them out of their tiny plastic pots last spring. My year of wandering and of filling my days however I choose is coming to a close, but it doesn’t feel like an ending. Instead I’ve spread out into new soil, a bigger patch, more sun. Today I start a brand new job working for an organization I much admire: the Wilderness Land Trust, dedicated to shoring up and expanding federal wilderness by purchasing private inholdings and rehabilitating them to their natural state before transferring them to the custody of federal agencies. The work is direct, non-partisan, and urgent—and will afford me plenty of travel along my beloved Rocky Mountains, which now constitute at least 10% of my heart. I feel so lucky to be joining this incredible team, and not at all surprised that my new coworkers have interests and passions as eclectic (and outdoorsy!) as my own. It feels like I’m joining a trail family, by which I mean my whole self is welcome. It was the easiest website bio I have ever written because I didn’t need to mimic what others wrote to fit in. I wrote what I wanted, and then found it was already in harmony with what the rest of the team has done. (That it felt so blessedly, sweetly jarring may tell you all you need to know about past experiences with “fit.”)

I feel simultaneously like I’m coming down from the Mountain (à la Thomas Merton) and like I’m trying to catch a merry-go-round that is spinning at a steady clip. I will be back among the 9-5’ers, back in the email and calendar and staff meetings and board meetings and deadlines and plans. I will get to do important work in good company. I will again be on a dedicated team, doing things none of us could do alone. And the creative things I’ve been doing these past six months since coming home from the trail will also now gain new vigor by fitting into a new frame, becoming daily healthy treats instead of the main course.

To my delight and surprise, I am giddy and eager to get started, a feeling I didn’t think I would ever again be able to summon about paid work when I was in the throes of burnout last year. I’ve spent some time in the past couple of weeks sorting out my desk and experimenting with different iterations of my morning routine. In the interest of good mental hygiene I’ve journaled about how I deal with stress and ambiguity, but I don’t feel anxious about this new chapter. Instead I feel grounded in the richness of life, not only from the countless hours under the sun and stars on the Long Hike but also from the months of free time at home since then.

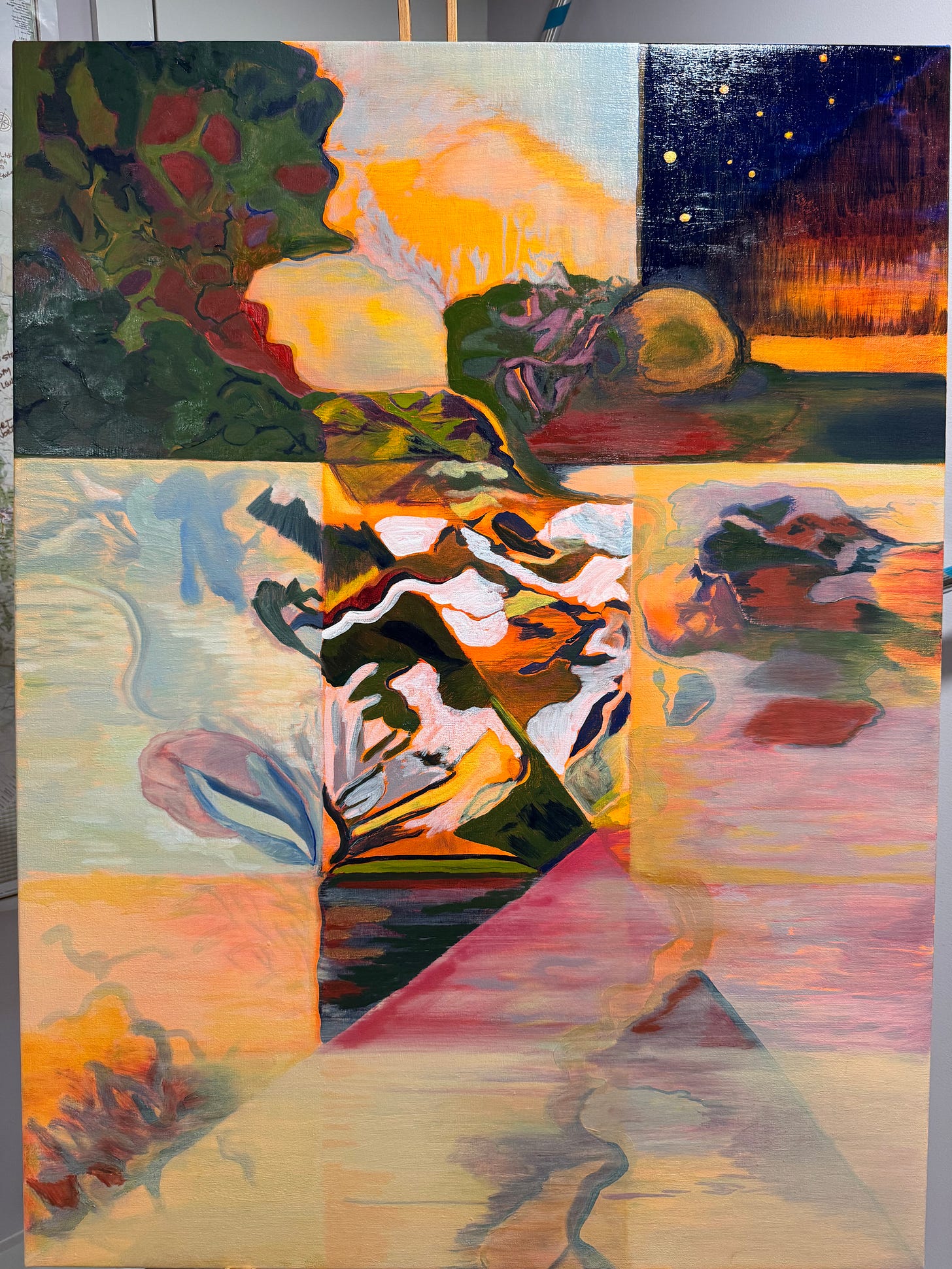

I’ve completed the big painting I spent the final month on the CDT imagining, and while of course no painting or novel or any creative project ever turns out exactly as we imagined it, I like the real thing that emerged better than the glowing vision in my head. At 30” by 40” it’s the biggest canvas I’ve ever worked with. It is too big to be taken in at one glance when I’m standing in front of it, so that it operates for me more like a place I visit than like a two-dimensional image, and yet it is made up of hundreds of particular choices. (I’m sharing it below in its still-drying, unvarnished, poorly photographed state because if I’m allowed to paint then you are, too. We don’t have to be Van Gogh to be allowed to make art.) Fuzzy feelings must eventually be made concrete. Likewise in both my book draft about the experience of hiking the CDT and in my novel in progress I’ve made great strides in the past six months from broad, ambiguous strokes to clear paths forward, from vibes to character arcs to technical issues to solve. The documents are now in a state where I can visit them day by day and dwell in them, laying down another thousand words in the hobbyist’s way, on the margins of the day.

Choices must be made, one way or another, for any project to become real—the hypothetical greatest American novel in one’s head is of no use in its perfection because nobody can read it. But for years I “worked on” the novel without being willing to make choices, instead proceeding in a meta fashion, writing countless words about the book instead of the thing itself. I have a shoebox full of notecards, five notebooks, and a printout of an old first draft of chapters 1-3 that have clarified (I hope permanently) to me that without being willing to make a choice—even a wrong one—nothing can actually happen. My book drafts are two big heirloom carrots growing under the surface where nobody can see them except for their frilly green hairdos. They are so much more than they seem, and are stronger for the resources I’ve given them this past half year. They do better when they are either lying in wait for me—their roots air-pruned, bracing for new soil to appear—or spreading out into new, loose, rich soil. They are ever so grateful not to be forever spinning in notebooks, their tiny roots spiraling round and round the edges of containers that no longer meet their needs but which they cannot escape.

After literal decades of making excuses to myself about why I wasn’t writing what I said I wanted to write, I learned very directly that having all the time in the world to write doesn’t make it any easier. It turns out there is always time, because even the most prolific novelists struggle to keep their butts in their chairs for longer than a couple hours a day. The trick is mainly in showing up. More to the point, for my ADHD brain if the goal for the day is “work on book,” I’ll struggle even in the absence of paid full-time work, finding a thousand chores and projects to do instead. But when the goal is “live a balanced day that has at least a little bit of all the things you need and want,” things go better. My writing comes closer to the prose of my dreams when I let it sneak up on me through the frame of my routine than when I try to stare it down in the gleaming laboratory of an otherwise empty day. Just as with the big painting, which has involved more hours of standing and staring at it between chores (and envisioning it through closed eyes as I fall asleep) than of handling brushes and paints, the books make themselves in my mind as much as through the pen and keyboard.

In order to actually write rather than endlessly outline and dither and analyze a text that doesn’t yet exist except in the negative, one must get speedy and casual about forks in the road. One must be sufficiently unburdened by one’s own expectations to actually choose a word to come next, and a word after that, and so on, knowing that even if none of these exact words make it to the final draft, even if we’re now only walking vaguely parallel to where the finished trail will be, there is no path to that final version except by closing off a million other possible paths. A hundred thousand words in notebooks that boil down to “or maybe Alan isn’t related to Lionel at all, or maybe they are secretly twins, or should Alan be imaginary?” are as good as zero words if we’re talking about a working draft because they live outside the alleged text. If I can’t make a decision about what is happening, nothing can happen next.

On the other hand maybe it was exactly the decade-plus of dithering, of being unable to foreclose any of a hundred interesting ideas about who the characters are, what they want, and what they do in reaction to each other, that finally showed me how something can be at once arbitrary and essential. It doesn’t matter what I choose because every possible choice has already played out in some alternate dimension. My subconscious mind knows all the possible things that could unfold, and now my conscious mind knows that it is the choosing that matters more than the choice. Any choice we make will be ours, and suffused with the rules of the universe we have made (my unconscious and I). It’s not unlike hiking the Continental Divide: it doesn’t really matter where the official trail is because the infinitely variable journey through its 50-mile-wide corridor will amass to the same big picture as everyone else, while at the granular level the path is wholly my own.

If the Appalachian Trail is like writing a series of essays on prescribed topics and the Pacific Crest Trail is paint by numbers, the Continental Divide Trail is like painting a mural on a snow fence using several partial buckets of paint you found in an abandoned gas station, with the only instruction being “tell a mountain story.” It’s somehow easier to do that if you are simultaneously trying to get to Canada before the snow flies than if you merely sat by the fence for five months. (Let’s not stretch the metaphor too far except to say please imagine the fence is movable, and shows up at the end of every long mile day. There is no going backward in thru hiking.)

What a year it was!

I have so much to show for my “year off” even though I entered into it with minimal expectations. I flipped over the table of my old life and headed into wilderness, and while I was out there I learned which parts of my old life are worthy of carrying into the future. I basked in my freedom and chose the things that matter to me: books, art, music, people, good food, big ideas, democracy, freedom. And now here I am, a humming and happy machine, not only rested and refreshed but finding myself with capacity to spare, ready to commit myself to something bigger than myself. I have walked my way out of extremes, out of all-or-nothing thinking, out of the idea that life should be a series of monoliths, that we’ll have fun when we’re old or that I’ll make art when I don’t have work anymore. I’m heading into a life that will be busy by my own choosing, not a life thrust upon me by a long-past self whose ambitions no longer match my lived reality. I’m not stopping all the things I’ve been doing and making, but adding a new path in parallel to be walked every day like the others. I have the amazing good fortune, it turns out, to be a mammal with free will, allowed to consent or not to whatever it is that others think I should be doing, allowed to do whatever I wish during my time on this planet so long as I’m willing to accept the consequences and opportunity costs. And so are you.

What a lucky thing to know. I hope the knowledge will stay, ambering eventually into wisdom that lives in my body as much as my mind. I’ll be here in the garden with the other carrots all in row, but wild in my heart just like them. And sometimes, now and then, we’ll reach ourselves back out to the margins again, or send our seeds sailing on the wind to see what they can discover. All in good measure, each cycle from seed to seedling to harvest to fallow to sprouting again, unfolding in its own time, while the earth keeps spinning. Here I go, leaping onto it from a running start!

good luck with the job

and

thank you